For all the meetings, presentations and reports from embedded academics and industry groups, purporting to show success against Salafi-Jihadi groups, the movement is still comfortably able to disseminate content through Swarmcast2.0.

The Western metanarrative has long been accepted by the orthodoxy of Terrorism Studies. However, while claims of success resonate at events hosted by industry funded bodies, the challenge encapsulated by Swarmcast2.0 remains. Salafi-Jihadi groups and the media mujahidin maintain persistent networks which function across multiple platforms simultaneously.

As argued previously:

If Terrorism Studies and policy makers continue to buy into the ‘success narrative’, rather than grasp the increasing complex constant evolution of the Swarmcast2.0 there is an increasing risk that disruption efforts will be using Web 2.0 approaches in a Web3 world.

Facing Swarmcast2.0 requires clarity of thought

Salafi-Jihadi groups have continued their online da’wa efforts to reach their primary target audience. Meanwhile, Western claims such as “smaller platforms and social media services are where extremists moved to after being shut down by giants like Facebook and Twitter”, belie the networks of supporters which operate across major social media.

One aspect of the metanarrative which is worth highlighting is the extent to which industry groups have emphasised the line that Salafi-Jihadi groups have been forced to use smaller or niche platforms. There are a number of problems with this idea, which have been discussed in detail elsewhere.

Two, however, are of particularly note. First, an issue of scale, that Salafi-Jihadi preferred platform Telegram has a vastly larger userbase than the so-called ‘giant’ Twitter (now X). Second, Meta owned WhatsApp has in excess of two billion users and is an internet giant but any estimation. In spite of the metanarrative claiming the ongoing success of driving Salafi-Jihadi to smaller platforms, Salafi-Jihadi material can be easily located on WhatsApp. This content is from groups including AQ, HSM, IS, Taliban, Hamas, and a range of channels which are theologically aligned but not branded as supporting a specific group that westerns have labelled a foreign terrorist organisation.

When narratives combine

The easy accessibility of content on the largest platforms should cast doubt on the Western metanarrative about success against Salafi-Jihadi online. However, occasionally content sharing on platforms such as WhatsApp also casts doubt on other elements of the Western metanarrative.

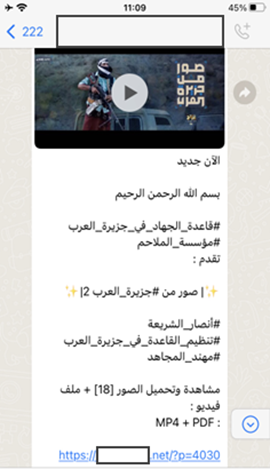

For example, Friday 21st July 2023, a WhatsApp group shared the video and pdf released with URL to the AQAP / al-Malahem website.

The screenshot of the release should provide the impetus for much needed reflection on important elements of the current success metanarrative.

First this is exactly the same domain as Tech Against Terrorism had previously claimed credit for removing, saying it was the fifth iteration of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s website to go down through their “engagement with infrastructure providers”. (their now edited post is available on Linkedin).

A month after the claimed disruption of that .net domain, it was still very much operational, and content was being pushed across multiple social media and digital channels.

The confusion that led a simple connection problem between an AQAP website and the Cloudflare service, to be valorised as a successful disruption effort, is a relatively basic mistake. However, it appears to be a genuine error which in the scheme of things is of relatively little consequence. Afterall, losing a URL at the rate of less than one per month is hardly going to break the media mujahidin.

Indeed the outage caused by the previous ‘successful’ disruption effort of the same AQAP website lasted less time than it took to send out the email announcing the ‘significant blow’ against AQAP.

The problem is less the specific claims and more the metanarrative to which it contributes. Elements of the largely Transatlantic orthodoxy of Terrorism Studies and CVE industry, often those working with large tech or social media companies, which have consistently claimed Salafi-Jihadi networks are being driven to increasingly niche and small platforms and their distribution capacity is being degraded.

At the same time, larger tech companies such as Meta are keen to point to the efforts made on other platforms, and the support given to smaller platforms through initiatives such as GIFCT and Tech Against Terrorism, and tools like Llama 2 which Meta made available intending it to support safer online interactions.

Indeed, there are also many complexities to be considered about what might be done about content in encrypted group chats, whether on WhatsApp, Telegram or elsewhere. However, the current efforts and complexity of considerations involved should not obscure the contemporary reality that WhatsApp groups are used to distribute Salafi-Jihadi material. Facing Swarmcast 2.0 requires clarity of thought, based on clear identification of the current way Salafi-Jihadi groups exploit web services.

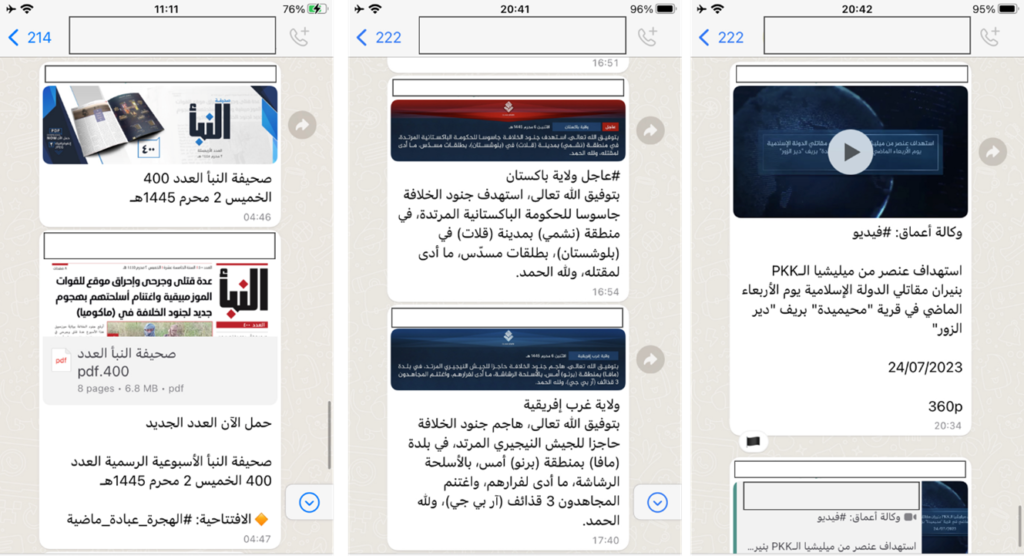

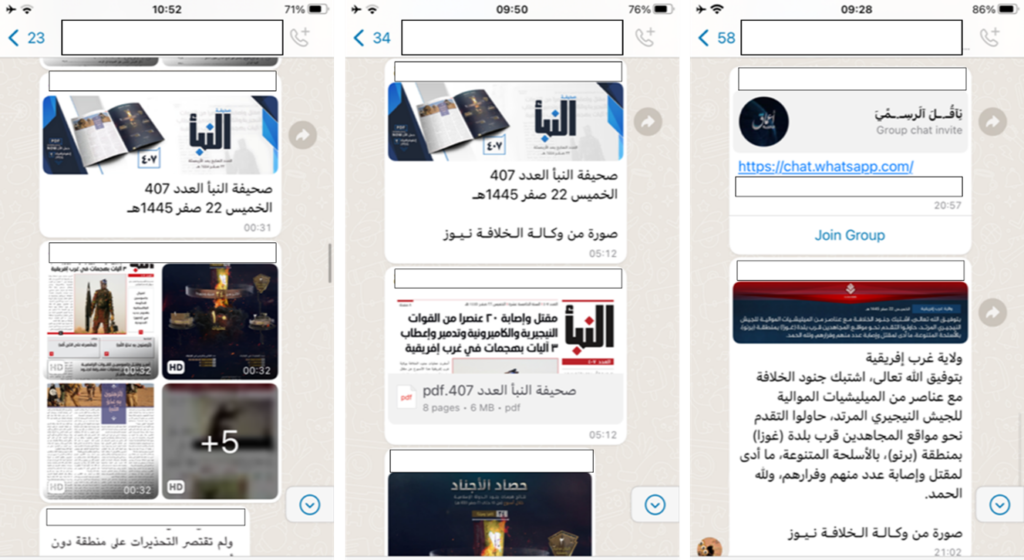

Examples of easily accessible branded content (Personal Identifiable Information and group names have been obscured).

IS

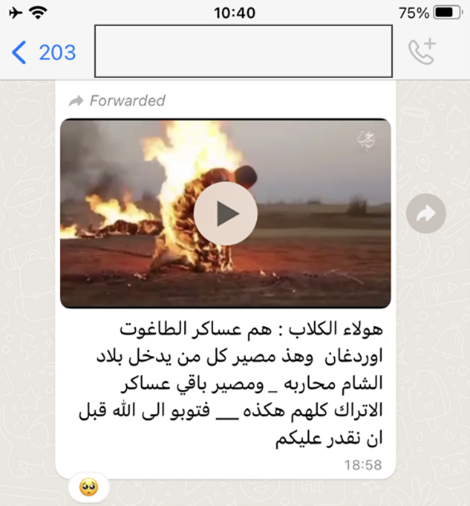

WhatsApp group members can also view some of the most brutal IS videos. Here, blow left, a section of a video showing Turkish soldiers being burnt alive. Right, a prisoner seconds before being executed by an IS child soldier.

AQ

These are just some of the many thousands of messages, videos and images observed over the last year of monitoring them on WhatApp. The use of WhatsApp as part of the Salafi-Jihadi multiplatform communication paradigm highlights need to break from the pseudo-metrics of the Western Metanarrative and focus on whether the movement is able to achieve their goal of distributing content to their primary target audience.

Since 2014, there have been those able to find pseudo-metrics through which to claim that a specific tactic had “degraded IS ability to … distribute content”. The result has been a metanarrative which interprets any development as evidence that the whack-a-mole approach is working.

As noted in a recent EICTP report on Swarmcast 2.0

The Salafi-Jihadi movement has continued its da’wa efforts despite repeated claims of success against the movement. We are now seven years after the claims that content distribution had been degraded, six years after the “purported resilience” of Salafi-Jihadi online networks was derided by those in the orthodoxy of Terrorism Studies, and three years after the supposed “full-fledged collapse” of IS media.

Furthermore, during this time the Salafi-Jiahdi movement has adopted a multiplatform communication paradigm and “the tech landscape has changed, some of what are referred to as ‘smaller’ and ‘niche’ platforms have become new ‘tech giants’,” a reality which poses a significant challenge to the metarnarrative of successful action driving the movement to smaller platforms.

Yet as Miron Lakomy put it in an article in Terrorism and Political Violence; “despite years of efforts from CVE stakeholders, the propaganda of militant Islamist VEOs is still easily accessible on the Internet”. This argument reiterates many of the findings of earlier work, including the article which first identified the mobile enabled Salafi-Jihadi Swarmcast. That 2015 article concluded that;

future policy to counter the dissemination of Jihadist content must challenge the Swarmcast on a strategic level. To be successful, strategies will need to take account of all three components of the Swarmcast when employing takedowns or other counter measures. his will mean focusing on strategic approaches to disrupting the system-wide emergent structures and collective behaviours rather than the tactical removal of individual accounts.

Eight years on there is little shortage of organisations announcing the latest ‘significant blow’ they have struck against Salafi-Jihadi groups or reporting the success of their projects. Commentators are frequently willing to report networks being “resolutely trashed”. Calls in various so-called ‘working groups’ are often witness frequent references to how busy people are and how much travel they are doing. However, despite the frenetic pace and the metanarrative of success, Lakomy’s study “effectively proves that the current approach to online CVE brought few tangible effects”.

A more strategic approach

Despite the best efforts of some commentators to talk up a success metanarrative about what has effectively been a decade long game of whack-a-mole, the current approach has consistently failed to make a significant dent in the ability of the Salafi-Jihadi movement to maintain a persistent presence, in either Swarmcast or Swarmcast 2.0 eras. As a result “these groups have been able to establish a solid foothold on the surface web”, according to Miron Lakomy.

Evidence that the world’s favourite social platform, with 2 billion users, is being exploited by IS, AQ, and the Taliban should undermine confidence in the claims commonly accepted in the transatlantic orthodoxy of terrorism studies and some parts of the CVE industry that Salafi-Jihadi groups have been pushed from so called tech giants onto smaller platforms.

Facing Swarmcast 2.0 requires clarity of thought, based on clear identification of the current way Salafi-Jihadi groups exploit web services. Media Mujahidin have achieved a persistent presence despite the ongoing efforts to disrupt their communication, due to the speed, agility and resilience of their networks coupled with the willingness to embrace emergent behaviours and web3 technology.

Instead, of playing whack-a-mole and developing tools which are well within the comfort zone of tech platforms, a strategic approach would focus on the elements of the Salafi-Jihadi information ecosystem which make them difficult to disrupt, specifically developing approaches that target the strengths of the media mujahidin and the Salafi-Jihadi movement. These may include;

- Judging success less by what western-centric commentators are able to locate and focus on the ability of the Arabic speaking primary target audience to access material.

- Targeting the key nodes within a dynamic multiplatform information ecosystem rather than static lists.

- A Web3 strategy – The Salafi-Jihadi movement already has adopted Web3, but disruption efforts lag far behind.

- Committing to lengthy periods of action – The Salafi-Jihadi movement are more than prepared for ‘days of action’, wearing them down will take weeks of sustained action forcing them to burn through manifold social media accounts, domains, phone numbers and email addresses.

- A paradigm shift to sustained multiplatform action – The Salafi-Jihadi movement are more than prepared for action against their presence on a single platform. Their Multiplatform Communication Paradigm provides resilience against efforts on any individual platform, as Salafi-Jihadi supporters like average social media users, have accounts on multiple platforms. Losing accounts on one platform only requires reconnecting via links shared on a second or third platform.

In 1999, Darcy DiNucci predicted, “the relationship of Web 1.0 to the Web of tomorrow is roughly the equivalence of Pong to The Matrix”. As technology continues to develop, the modus operandi of the Media Mujahidin evolves with it. A Web3-enabled Swarmcast2.0 has arrived. Swarmcast2.0 is much more dynamic, secure, encrypted, decentralised, and resilient than the original version which emerged by 2014. The understanding of the challenge posed by the Media Mujahidin must likewise evolve if we are to avoid trying to play Pong in The Matrix.