Captagon is the brand name given to the synthetic-produced drug based off of fenethylline molecules. Firstly synthesised in Germany in 1961, it was introduced as milder alternative to amphetamine and methamphetamine that were employed at the time to treat narcolepsy, fatigue, behavioural disorder and minimal brain dysfunctions. It was also used in lack of drive, particularly in elderly patients due to organic diseases (like Parkinsonism) or other causes, as well as after severe illness or injury.

Captagon manufacturing ceased in the 1980’s as a consequence of the UN convention that banned the fenetylline component. Following police operations that hit labs located in Eastern Europe and Turkey, with the follow-on effect of disrupting the established market, the production moved southward. Under the initial direction of criminal networks from Bulgaria and Turkey, Captagon center of gravity transitioned to the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula.

After the authorized production ended, the substance is currently being manufactured in a counterfeited manner, with the addition of other chemicals that can empower the effects.

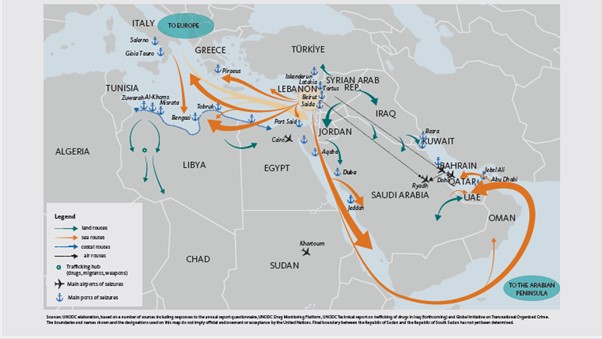

The main trafficking routes

Source: UNODC World Drug Report 2022

Source: UNODC World Drug Report 2022

After the crackdowns on labs and the production processes in Eastern Europe and Turkey, fenetylline stocks that remained in Europe were largely destroyed, although some of them were trafficked to and sold on the black markets in the Middle East: so much so that the current production sees the Levant as the epicentre of the illicit trade.

As the map shows, from that area a progressively massive use has spread all over the Greater MENA quadrant ever since, finally reaching the Saudi Arabia peninsula and some other Gulf Countries. The main hubs are currently represented by Lebanon and Syria which, due to their role in the enterprise, have evolved in narco-states of sorts that have almost monopolized the Captagon business: this outcome has been furthered by the connections established between non-state entities (either producers, smugglers or users) and state actors that have emerged as a consequence of the profitable initiative.

Captagon producers in Lebanon are mainly located in the areas of the Bekaa Valley, a strong hold where several illicit activities are being carried out by sub and non-state actors that take advantage of the scarce presence of the Country’s security forces. Large quantities of pills are being manufactured and smuggled from there: the Black Desert, a strategic transit area that stretches over the borders of Jordan, Syria and Saudi Arabia, has emerged as the critical node of the trafficking. Moreover, that the Valley may have been identified as a production spot for Captagon cannot be surprising given the well know involvement of Hezbollah in the drug trade. This situation lends also credit to the assumption that even the Iranian regime may be somehow involved in the deal: an example can be found in Iraq, where Iranian made crystal meths have preponderantly invaded the marketplace, as the massive quantities recovered and seized by local police forces as a consequence of counter-narcotics operations can prove.

On the other hand, the conditions generated by the civil war in Syria has set the conditions, amongst other nefarious effects, for some areas of the Country to become a breeding ground for the production of Captagon.

The proximity of the local production and low prices – if compared to the cocaine trade (massively produced in another continents, with a wider trafficking span and significantly higher in price) – are deemed conducive factors for the prevalence of Captagon in the concerned zones.

As an example of the magnitude of the effects of the wide-spread use of the narcotic in one of the major state of destination, a survey executed in 2015 by the Secretary of Saudi Arabia’s National Committee for Narcotics Control reported that the majority of the kingdom’s drug addicts were between 12 and 22 years old, with at least the 40% of them addicted to Captagon. Other Gulf States are also affected by the almost endemic use of the substance: as the results of police operations can demonstrate, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain are heavily exposed to the threat.

Even in Egypt, local authorities have raised an alert in connection with the influx of synthetic drugs, like Captagon, a situation that has not only changed habits in the youth, but it is also fuelling crime.

Some investigations have shown how Libya is being employed as a staging/transiting area by virtue of the well-consolidated trafficking routes that lead to the Sahel region, a likely new open market for Captagon. By digging into the issue, though, it is not surprising that Libya is being involved with this respect, especially due to the presence, both in the East and the West, of Syrian mercenaries[1] who may be playing a remarkable function in the business.

Finally, recent indicators have referred to Sudan as another hot spot where Captagon is not only being smuggled but also supposedly produced.

Evidence

Over the last decade, several interdiction operations have been executed by customs and law enforcement agencies in concerned areas:

- October 2015, a member of the Saudi Royal family and four others were detained in Beirut on charges of drug trafficking after airport security discovered 2 tons of Captagon pills and some cocaine on a private jet scheduled to depart for the Saudi capital;

- November 2015, Turkish authorities seized 2 tonnes of Captagon during raids on the Syrian border;

- December 2015, the Lebanese Army discovered two 2 scale drug production workshops in the north of the country: significant quantities of Captagon pills were seized;

- May 2017, French customs at Charles de Gaulle airport seized 750,000 Captagon pills transported from Lebanon and destined for Saudi Arabia;

- January 2018, Saudi Arabia seized 1.3 million Captagon pills near the border with Jordan;

- December 2018, Greece intercepted a Syrian ship sailing for Libya, carrying 6 tonnes of processed cannabis and 3 million Captagon pills;

- July 2019, a shipment of 33 million Captagon pills, weighing 5.25 tonnes, was seized in Greece coming from Syria;

- July 2019, 800,000 Captagon pills were found and seized on a boat in the UAE;

- August 2019, Saudi customs at Al-Haditha seized more than 2 and a half million of Captagon pills found in a truck and a private vehicle;

- February 2020, the UAE found 35 million Captagon pills in a shipment of electric cables from Syria;

- April 2020, Saudi Arabia seized 44.7 million Captagon pills smuggled from Syria;

- November 2020, Egypt managed to seize 2 shipments of Captagon pills coming from Syria, the first with more than 3 million of tablets, while the second with more than 11 million tablets;

- December 2020, Italian authorities seized about 14 tonnes of Captagon arriving from Syria and heading towards Libya, including about 84 million pills, worth around $1 billion;

- January 2021, Egyptian authorities seized 8 tons of Captagon from a shipment which arrived from Lebanon;

- February 2021, Lebanese customs seized a shipment of 5 million Captagon pills hidden in a tile-making machine, intended for Greece and Saudi Arabia;

- April 2021, Saudi authorities discovered more than 5 million of Captagon pills hidden in fruits imported from Lebanon;

- February 2022, Greek confiscated nearly 100,000 pills of Captagon meant to be shipped to ISIS fighters in Syria.

Nexus with terrorism

Sources have indicated that Captagon use is prevalent on both sides of the conflict in Syria; as mentioned earlier, in Lebanon Hezbollah fighters, linked to Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and Iran, are thought to be consuming and manufacturing the synthetic drug as well.

The narcotic has long been popular with Islamic extremists and terrorists: even though solid evidence are still to be produced, it is commonly understood that ISIS militants may be using Captagon (and tramadol) to enhance their performance. One indicator of it can be found in the outcomes of Free Syrian Army clearing operations in ISIS strongholds in Syria whereas it has been reported that ISIS-manufactured pills were initially smuggled from Iraq, and were known as “Fallujah” pills. After disappearing from the market, a new type of pill manufactured in Syria started showing up. Even the Syrian Democratic Forces, after liberating areas in the northern part of the Country, managed to find boxes of Captagon pills left behind in ISIS bases, homes of fighters and on the bodies of the dead militants. It got also reported that wounded jihadists did not exhibit signs of pain if compared to seriousness of their wounds, allegedly due to the their bodies being under the effects of the drug. Likewise, in Europe clues of the possible ISIS involvement were discovered as demonstrated by the seizure of Captagon pills as a consequence of the site exploitation executed by the French security forces against one of the hideouts in Paris belonging to the terrorists who carried out the Bataclan attacks in November 2015.

Given the situation, analysts have inferred that, because of the spread of the narcotic in concerned areas, ISIS may be looking into entering the illicit trade in order to add the Captagon smuggling into the funding toolbox aimed at financing violent activities, as the organization has already done with other lucrative illicit undertakings like trading in oil, looting antiquities and smuggling migrants.

Another indicator that cannot be dismissed and that provide credibility to the hypothesis that ISIS or other violent jihadists organizations may be taking advantage of the drug trade for financial purposes is that these organizations are purportedly not alien in being involved in such a business in other hot spots like in the bordering areas between Libya and the Sahel region: the local AQ associated movements[2] are notorious for being implicated in the activity in a mutual connection with smugglers belonging to the local nomadic communities.

Conclusion

What is manifest is that the whole Captagon trade cycle – production, trafficking, use, incomes investment – is the result of freedom of movement, connections and flows enjoyed by the illicit networks. Difficult terrain, porous borders, lack of (or dirty connections with) state-related security structures, depressed economy, poor health systems, are all factors that hamper the provision to the local population of state-based services. With this respect, the void of sovereignty due to the lack of governmental control is being opportunistically harnessed by mainly informal violent players that are capable of taking advantage of the precarious conditions, by exploiting vulnerabilities and by exercising state-related functions. The setting of “organized entropy” that is typical of the irregular warfare operational environment is precisely the milieu where the phenomenon under scrutiny thrives as one of the constituting components of the (in)security-related hybrid eco-system we are living in: a mix of state, sub-state and non-state entities (often assisted by external influences) like criminal cartels or terrorist networks, sometimes in a “nexus” operational mode[3] have been challenging state-provided security and stability by competing against weak or absent governments over resources and the relevant population. Thus, by taking advantage of the produced chaos, violent actors are able to seize, retain and exploit the initiative in order to achieve a position of “relative superiority” against opposing actors (national and international) with the goal of maintaining the illicit gains. The situation represents one of the security paradigms that we, as the international community, are inevitably framed within and that we have been and will be facing for the years ahead in light of the undesired effects that we will be exposed to – both directly and indirectly – when it comes to determining the posture and the measures to effectively counter it.

[1] Employed by both Turkey and Russia in support of their agenda in the Country.

[2] Field studies have covered the involvement of the Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Movement for Monotheism and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) in criminal drug trafficking: it has been assessed that the business model changed over the time from charging traffickers for passing through the territory they controlled to providing armed escorts to drug convoys in so doing gaining between 10 to 15 per cent of the value of the narcotic.

[3] The UN Security Council Resolution 2482 (2019) has addressed the issue of the “nexus” between terrorism and organized crime, even with respect to the relevancy of the drug trade in terms of source of terrorism financing.