The attack against President Trump has brought to the surface once again the issue of political assassinations. The United States of America is not immune as a country to such events in its political history.

Continue readingAll posts by Marco Lombardi

Paris Olympic security threats: Why the Islamist terror network and Hamas matter – by Maria Alvanou

The world’s eyes in about a month will be on France hosting the Paris 2024 Olympic Games. Major athletic events should always be considered a possible target for terrorists and a challenge for law enforcement authorities that have to safeguard security, making sure at the same time that people can enjoy participating with a festive spirit.

Continue readingThe role of local journalism between the need for security and new crises – by Giacomo Buoncompagni

Recent national and international emergencies, from pandemics to the recent floods, have repeatedly highlighted how the role of local information must be to synthesise the various social and cultural policies proposed by public bodies and the correct representation – the state of life of citizens in the territory – beyond national media logics, often based on speed and the spectacularisation of disasters.

Continue readingFrom Heroes to Targets: The Dual Impact of MMA in the Caucasus Region. Investigating the MMA-Terror Nexus– by F. Borgonovo and G. Porrino

Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) has become a prominent sport in Russia, with a fervent following in the Caucasus region. This surge in popularity can be attributed to a blend of cultural heritage, historical precedence, and socio-economic factors that have made combat sports an integral part of Russian society. However, the rise of MMA has also brought about significant security challenges, with extremist groups exploiting the sport for recruitment and propaganda purposes. This report provides an in-depth analysis of the factors driving MMA’s popularity in Russia and examines the associated security risks. Russia boasts a long-standing tradition of martial arts, with Sambo and Judo being the most prominent disciplines. Sambo – self-defense without weapons – was developed in the Soviet Union in the early 20th century. It was designed to improve hand-to-hand combat capabilities for the Soviet military and law enforcement. Judo, introduced to Russia in the early 1900s, has also been embraced for its effectiveness in real-world combat and its emphasis on discipline and respect. These martial arts have not only shaped the training regimens of the Russian military and police forces but have also permeated the civilian sporting culture. The skills and values instilled through these disciplines have created a fertile ground for the acceptance and proliferation of MMA, which combines techniques from various martial arts, including Sambo and Judo.

In economically challenged regions, particularly within the Caucasus, MMA offers a viable route to fame and financial stability for many young men. The sport’s growing popularity has led to the emergence of local and international competitions, providing fighters with opportunities to showcase their talents and earn substantial incomes. Successful fighters often rise to the status of local heroes, serving as role models and sources of inspiration for the youth. Khabib Nurmagomedov, a native of Dagestan and a former UFC Lightweight Champion, epitomizes this phenomenon. His success on the global stage has not only brought pride to his home region but has also motivated a new generation of fighters to pursue careers in MMA. This aspirational pathway is crucial in areas where economic opportunities are limited, and the prospects of upward mobility are constrained.

Recognizing the potential of MMA to foster community engagement and provide economic opportunities, local governments and private sponsors have extended significant support to the sport through national and international events (such as UFC and Bellator). Investments in training facilities, sponsorship of events, and financial backing for athletes have created a robust infrastructure for the growth of MMA. This support system ensures that talented fighters have access to the resources they need to train effectively and compete at the highest levels. From the side of the members of these communities, it is important to notice a vibrant digital environment in which Fighters and fans actively use social media to share their training, fights, and personal stories, building a strong and engaged community.

On the one hand combat sports provide a way out for members of marginalized classes, on the other hand, they become hotbeds from which terrorist organizations recruit. Chechnya, Dagestan, and Ingushetia have been the main supplier regions of foreign fighters for several jihadist organizations including the Emirate of Caucasus and Islamic State (IS). If we systematize the Islamist attack in Dagestan on 23 June 2024 and the attack on Crocus Hall in Moscow, we note how IS and the linked jihadist organizations are successfully weaponizing subjects from ethnic groups living in Russia who suffer socio-religious marginalization. These populations include Tajiks, Uzbeks, Chechens, Ingush and Dagestani. In this case, tapping into MMA gyms allows organizations to recruit “already trained” individuals, and public events such as tournaments and matches become useful moments to widen the network.

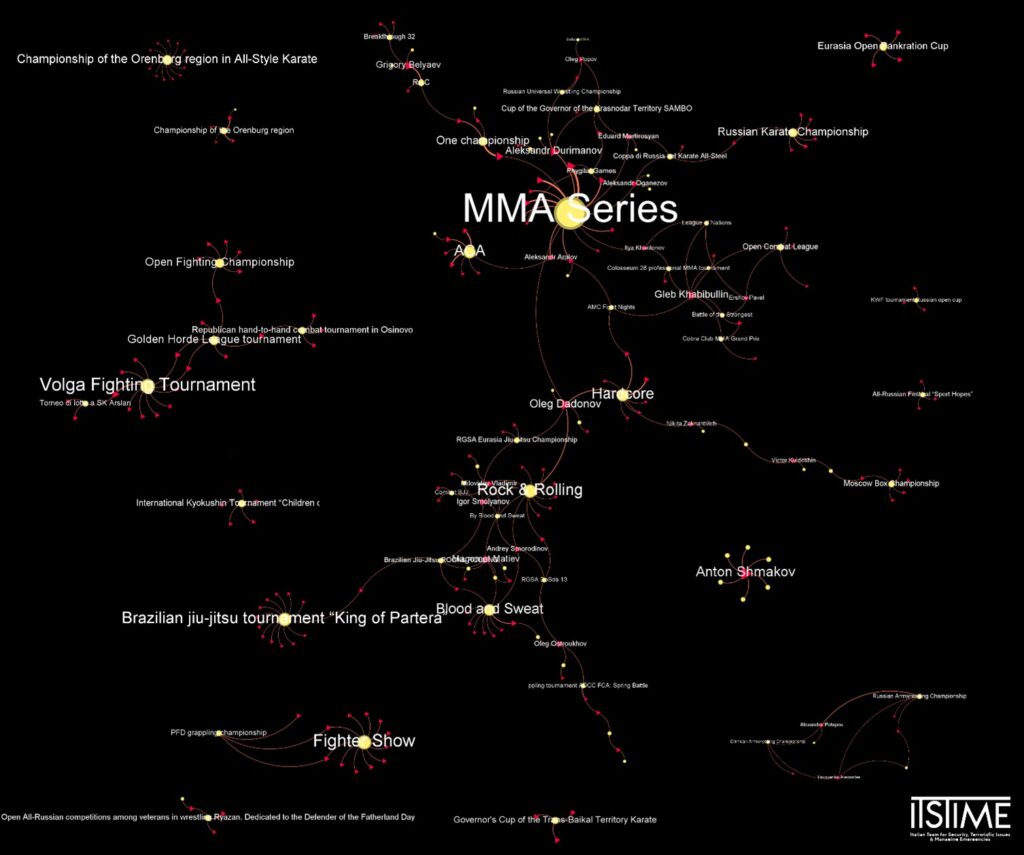

Not only the Islamic State – a study on PMC Wagner recruitment ecosystem:

Islamic State is not the only organization exploiting the combat sports environment. Our recent study on PMC Wagner reveals how this actor has built an effective system of promotion, propaganda and recruitment through combat sports. After investigations into Wagner recruiting centers which take the form of gyms and fight clubs, data about tournaments and fighters involved were extracted. The first evidence of the analysis reveals how MMA competitions are the major promoters of pro-Wagner events. Wagner’s recruitment strategy involves organizing and promoting MMA tournaments that serve as platforms for propaganda. Fighters associated with Wagner participate in these events, which are extensively covered on social media, further amplifying the group’s reach and influence. PMC Wagner has created a recruitment network both offline and online embedded with extremism ecosystems (far-right, ultranationalist, jihadist) and pro-violence communities.

Recent evidence and analysis clearly show that terrorist groups are increasingly targeting the combat sports environment, yet efforts to monitor these activities remain insufficient. In Russia, the strong presence of combat sports and the marginalization of certain ethnic groups have made socio-economically fragile but highly trained individuals attractive targets for extremist recruitment. This troubling intersection of combat sports and extremist recruitment is not limited to Russia. Similar trends are emerging in the West, where white supremacist groups in the U.S. and Europe are utilizing MMA clubs as recruiting grounds. The Azov Battalion, for instance, has been linked to MMA fight clubs affiliated with the European far-right, illustrating the global dimension of this issue. The proliferation of Active Clubs in the U.S. and Europe, which merge martial arts training with white supremacist ideologies, further emphasizes the extent to which combat sports are being co-opted by extremist groups. These clubs provide marginalized individuals with a sense of community and purpose, only to indoctrinate them with extremist ideologies and train them in combat techniques.

Attentati Daghestan 23 giugno 2024 – by Giovanni Giacalone

L’attentato islamista di domenica 23 giugno in Daghestan ha causato la morte di 15 appartenenti alle forze di sicurezza (Polizia e Guardia Nazionale), due civili (tra cui il sacerdote Nicolai Kotelnikov, sgozzato dai terroristi), oltre al ferimento di una trentina di persone.

Continue readingLa nuova strategia di Mosca in Libia: arrivano gli Afrika Corps – A. Bolpagni & G. Porrino

Mentre gli occhi del mondo sono concentrati sulla guerra in Ucraina e sul conflitto tra Israele e Hamas, la Russia sta riconsolidando la propria presenza in Libia, ponendo un’ulteriore minaccia al fianco sud della NATO. Nonostante la disfatta dell’alleato Generale K. Haftar nella battaglia di Tripoli nel 2020, la presenza russa è rimasta ben consolidata in relazione al più ampio progetto geopolitico di proiezione di potenza nel Sahel e nell’Africa sub-Sahariana.

Continue readingRussian sabotage campaigns: the new European front of the War – by G. Porrino & A. Bolpagni

Since February 2024, at least ten operations between arson attacks and train sabotage have been planned, several of which have been intercepted by the intelligence services of the countries targeted. Where operations were successful, pictures and related videos were disseminated on PMC Wagner’s main Telegram channels. Such acts of sabotage do not constitute an isolated case, but rather part of a broader operation.

Continue readingIslamic State Propaganda, Following the Content – by F.Borgonovo, S. Lucini, M. Lakomy

From 2019 to the present, the Islamic State’s digital ecosystem has undergone a dramatic evolution. Within the timeframe of 2021 to 2023, new players have come onto the scene, offering specialized translation services, while others have fortified the infrastructure for online dissemination, making it more robust against attempts to disrupt their activities.

Continue readingCounteR – uno strumento innovativo per rilevare contenuti online radicali

Si è concluso con successo il progetto triennale CounteR, finanziato attraverso Horizon 2020, il programma di ricerca e innovazione dell’UE. Il 30 aprile 2024 segna il completamento formale del progetto CounteR – Countering radicalisation for a safer world: privacy-first situational awareness platform for violent terrorism and crime prediction, counter radicalisation and citizen protection.

Continue readingSPOTREP: The first ever direct Iranian air attack against Israel – by Emilio Palmieri

Over the night of April 13, 2024, Iran launched a coordinated air attack against Israel by employing more than 300 armed UAV and dozens of missiles. The Israeli air defense architecture was able to effectively repulse the attempt.

Continue readingPMC Wagner recluta per l’Africa e Afrika Corps guarda al Niger – by G. Porrino e A. Bolpagni

Dalla fine di febbraio 2024, dopo un silenzio durato sei mesi, i vertici della Wagner hanno riavviato il processo di reclutamento per le operazioni in Africa e ad aprile 2024 Afrique Media, ha annunciato l’arrivo degli Afrika Corps in Niger.

Continue readingL’audio messaggio del leader delle Brigate al-Qassam: cosa significa? -by Giovanni Giacalone

A cinque mesi dal massacro del 7 ottobre Hamas ha diffuso un breve audio di 35 secondi nel quale Mohammed Deif, il comandante del braccio armato dell’organizzazione, le Brigate Ezzedin al-Qassam, esorta i musulmani a “unirsi alla lotta per liberare Al-Aqsa”. Il video è inizialmente comparso su Telegram ad inizio settimana per poi venire diffuso su tutta la rete.

Continue reading