Between May and October 2022, five supremacist or accelerationist attacks took place: On 14 May Payton Gendron in Buffalo (USA), on 4 July Robert E. Crimo III in Highland Park (USA), on 11 August Ricky Walter Shiffer in Cincinnati (USA), on 26 September Artyom Kazantsev in Izhevsk (Russia), on 12 October Juraj Krajčík in Bratislava (SK) and finally on 13 October Austin Thompson in Raleigh (USA). All the reported attacks impacted on the extremist digital ecosystem. In particular, the more violent extreme-right groups hailed the attacks and the attackers by recalling the exploits of Tarrant and other more notorious supremacist terrorists with a higher “killcount”. But the most interesting data concerns the action/reaction of the extremist community known as TERRORGRAM. A self-called collective of channels and chatrooms involved in spreading dissident ideas, glorifying terrorism, calling for violence, spreading extremist ideological material and demonising minority groups.[1] The collective operates as a loose network without having any formal affiliation with a specific group but well connected with several extremist organizations such as The American Futurist (closely linked to James Mason and ex-AWD members)[2], Ouest Casual (French extreme-right pro violence group) Ukrainian volunteers battalions and Russian mercenaries.[3]

The collective implements a practice known as “sanctification”. A socio-digital practice that, in the event of an accelerationist, supremacist or neo-Nazi attack, sees the members of the collective engaged in the search for elements attesting to the ideological and operational affinity with the narrative core of the TERRORGRAM in order to sanctify the attacker. The sanctification of a terrorist entails his entry into the pantheon of terrorist-saints that are taken as models by the TERRORGRAM.[4] Among these we can identify some who, by their history and modalities, can be considered as founders of the ideological core of the TERRORGRAM and therefore we define them as founding saints: Brenton Tarrant, Theodore Kaczynski, Anders Breivik, Charles Manson, Timothy McVeigh and Dylan Roof.

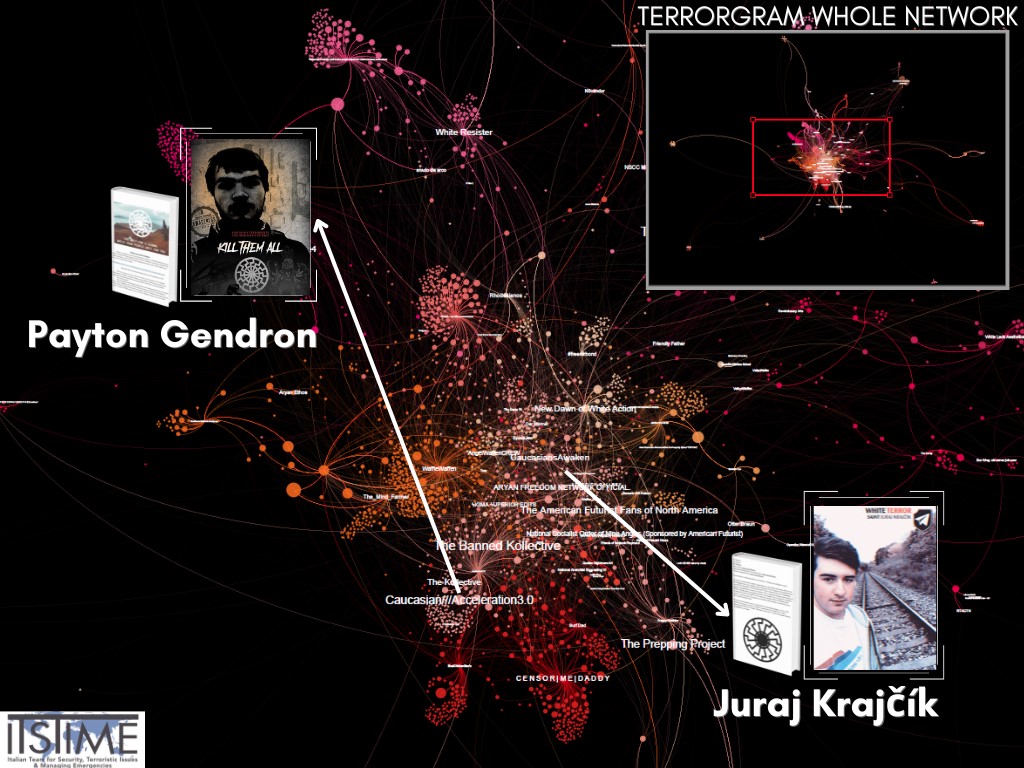

Regarding the 2022 attacks, only two were sanctified (and claimed) by the TERRORGRAM: Payton Gendron and Juraj Krajčík. The characteristics of these two terrorists that drove the collective to an almost immediate sanctification are:

- Publishing a manifesto, both made mention of being convinced (radicalised) online, but in particular Juraj Krajčík thanks TERRORGRAM for its ‘tactical guidance and inspirational art’.

- Extreme precision in target selection.

- Hitting a target that embodies the main enemy of the collective’s vision in this case of ethnic and gender minorities

of the three elements, the main one is the publication of the manifesto, while the choice to strike during a live broadcast (an action carried out by Payton Gendron but not by Juraj Krajčí) although it provides a powerful propaganda medium, is not a necessary condition for sanctification. Unlike the two completed sanctification cases, the other attacks however activated TERRORGRAM in other ways. in the case in Russia, some channels disseminated photos of the dead bomber showing the sweatshirt with the swastika, the attacks against law enforcement gave the pretext to relaunch excerpts from the work known as HARD RESET, a TERRORGRAM publication containing various articles, many of which were against law enforcement agencies described as “pigs”. From May to October of this year, we therefore observe how TERRORGRAM is getting closer and closer to the bombers themselves. If, on one hand, the terrorists are sanctified, on the other hand, the extremist collective also begins to be quoted and praised directly by the attackers. Finally, to analyse the morphology, organisation and socio-digital practices of the TERRORGRAM, a social network analysis was launched. In the merits of this article, the graph becomes useful in order to identify the size of the network and which actors (Channels, chatrooms and users) have relaunched the sanctifications that took place between May and October.

Graph 1: social network analysis of the TERRORGRAM with a focus on its core

[1] Jacob Davey et al., ‘A Taxonomy for the Classification of Post-Organisational Violent Extremist & Terrorist Content’, 2021.

[2] ‘What Is Siege Culture?’, accessed 24 October 2022, https://crestresearch.ac.uk/comment/what-is-siege-culture/.

[3] Data collected through digital ethnography applied inside private chatrooms.

[4] Graham Macklin, ‘“Praise the Saints”’, in A Transnational History of Right-Wing Terrorism, by Johannes Dafinger and Moritz Florin, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 2022), 215–40, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003105251-16.